Russian entrepreneurs who pour their hearts and dollars into projects learned long ago their success can evaporate in an instant on the whims of the country’s security services.

Now, foreign investors, previously seen as largely out of reach from such predation, are being confronted with the same reality.

The arrest three weeks ago of 51-year-old American Michael Calvey — Russia’s most successful foreign investor — may be a tipping point for foreigners doing business in Russia, say experts who follow the country’s increasingly uncertain business environment.

Consider this statistic reported by the Kremlin’s business ombudsman: more than 6,000 Russian entrepreneurs are now serving time in Russian prisons, many because the criminal prosecution service frequently involves itself in settling business disputes.

“It’s a story understandable by any Russian businessman for many years, but Western companies are now at exactly the same state,” says Andrei Yakovlev, a political economist at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, or HSE.

“I suspect we will see some kind of flight of foreign investors from Russia in terms of selling existing assets at quite low prices and taking clear losses.”

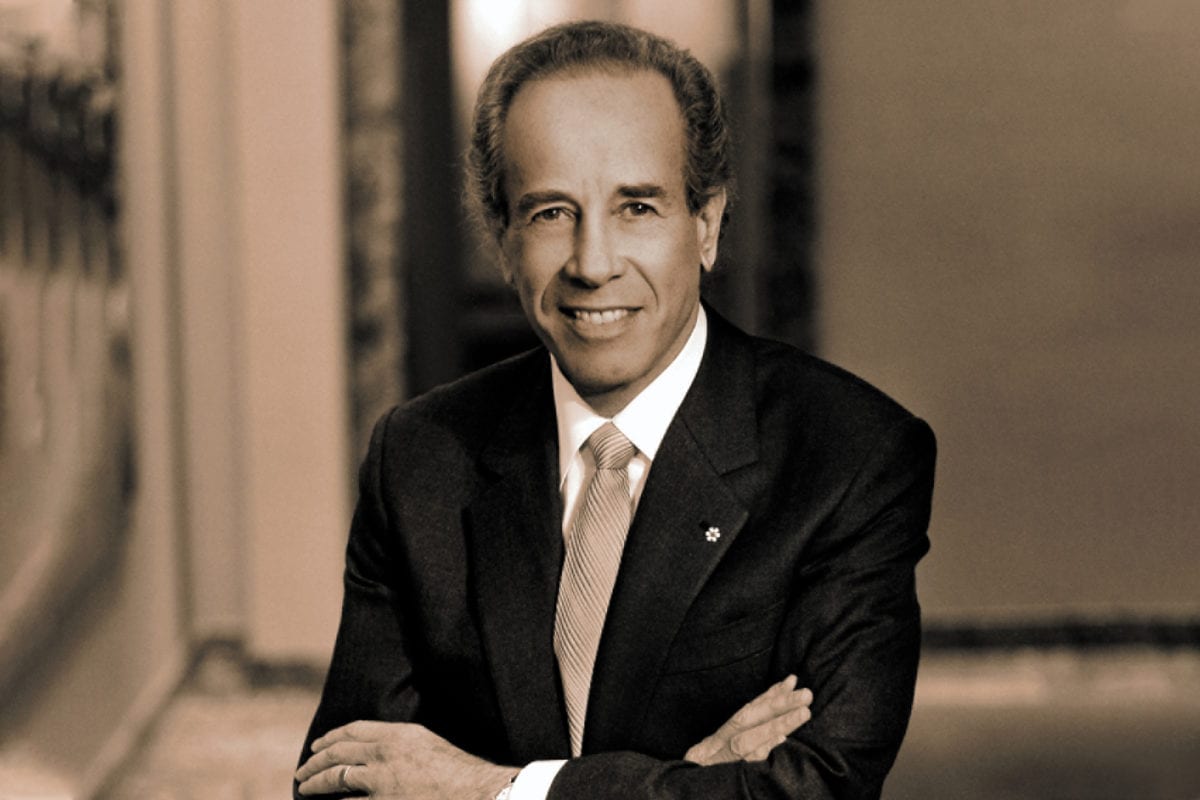

Calvey’s supporters want him released from custody and for there to be an independent review of the case against him. (Tatyana Makeyeva/Reuters)

While it’s certainly not unheard of for foreigners to be targeted by security services such as the FSB, successor to the old Soviet KGB, until now such cases have been unusual.

Perhaps the best known example is Bill Browder, the American-born human rights campaigner who ran a wildly successful Russian investment business until he ran afoul of President Vladimir Putin in 2008.

Still, the Calvey case has clearly unnerved foreign investors.

Twenty-five years ago, Calvey launched a Russia-focused investment firm, Baring Vostok, which went on to kick-start scores of Russian businesses, including tech giant Yandex.

Supporters say Calvey scrupulously avoided politically charged bets and kept good relations with the Kremlin during his long, successful career.

The criminal case against him appears to stem from what is essentially a shareholders dispute involving a Russian bank that Baring Vostok was heavily invested in. Prosecutors have charged Calvey with embezzling money by selling another company to the bank at an inflated price.

‘Ludicrous’

However, many business commentators in Russia suspect the prosecution is a shakedown by people linked to the FSB. By using the agency’s wide discretion to investigate and lay charges, critics argue, investigators could potentially use their power to seize the bank or other Baring Vostok assets.

The most notorious example of this critics cite is the tax-evasion prosecution of Putin rival Mikhail Khodorkovsky in the mid-2000s, which led to the break-up of his energy empire. Billions of dollars of his company’s assets were seized by state-owned companies.

In an opinion piece for Moscow’s Carnegie Centre, an independent political think-tank, former bank CEO Andrey Movchan called the accusations against Calvey “ludicrous,” noting that Calvey’s opponent, a fellow shareholder, has close family connections to the FSB.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a former oil tycoon who fell foul of Putin’s Kremlin, spent years in prison for tax evasion. (Dylan Martinez/Reuters)

Business columnist Andrey Sinitsyn went further. He suggested in Republic.ru that Russia’s “mafia state” is continuing its takeover of private business, putting Russia’s economy on track for a disastrous repeat of Soviet-style managed economy.

One of the key features of the economy of the Soviet Union was state ownership of most sectors of the economy, which led to extreme inefficiencies and stagnation.

Russia’s economy is already dominated by state-controlled enterprises — they account for up to 40 per cent of the country’s economic output, according to some estimates.

Climate worsens

Lev Lester, a Russian-American businessman who spent two decades working for foreign automotive firms doing business in Russia and now blogs about his insights, told CBC News the business climate in the country is growing worse by the day.

“Everyone thinks that bad things won’t happen to them. Everyone thinks, ‘I’m smart and experienced and careful. Bad things will happen to others.’

“But this is a mistake.”

He will sit in jail. It will be without end. No proof. No discussion.– Lev Lester, Russian-American businessman

He predicts pleas by Calvey’s supporters for him to be released and for his case to be reviewed will go nowhere.

“He will sit in jail. It will be without end. No proof. No discussion.”

Large Canadian firms doing business in Russia are represented by CERBA, the Canada Eurasia Business Association based in Moscow. Its membership includes Montreal-based Bombardier and global mining giants Kinross and Barrick.

In a statement emailed to CBC News, CERBA chair Nathan Hunt said “the Calvey case appears to be a step in the wrong direction.”

Hunt said while Russia has made great strides in improving the investment climate over the last decade, CERBA is in favour of “strengthening the rule of law in Russia.”

The group called on Putin to conduct an independent, objective review of the Calvey case.

Mixed messages

Five days after Calvey’s arrest, Putin used his state of the nation address to proclaim that Russian courts shouldn’t be used to settle business disputes because it’s detrimental to the economy.

But just days later, his spokesman said Putin wasn’t going to interfere in the Calvey proceedings. He’s had nothing to say about the case since.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has given mixed messages about the Calvey case. (Pavel Golovkin/Pool via Reuters)

To many in the West, it may seem as though Putin is the only authority that matters in Russia, but political economist Andrei Yakovlev says the reality is more nuanced.

He says it’s more often the case that competing groups or cliques vie for influence within Russia’s ruling class, with personal loyalties and informal alliances often determining who gains Putin’s ear.

FSB becomes more assertive

Up until around 2008, Yakovlev says, an improving Russian economy, fuelled by high oil prices, created positive conditions for those within Russia’s government who favoured more openness and collaboration with Western investors and companies.

But when Putin returned to the presidency in 2012 after a four-year hiatus, the climate had changed for the worse.

Russians took to the streets in protest of deteriorating economic conditions. And events abroad, especially the Arab Spring uprisings, unsettled many in Russia’s leadership.

Yakovlev says the result was Russia’s security services became increasingly assertive — a trend that has grown more acute as relations with Western nations have deteriorated.

Falling fortunes

Even before Calvey’s arrest, successive rounds of European, Canadian and U.S. sanctions had worsened the investment climate in Russia.

The Financial Times reports that net direct foreign investment fell to $5.7 billion US for the first three quarters of 2018, compared to nearly $27 billion for the same period in 2017.

It’s not clear the Kremlin leadership has a plan to make up for the lost opportunities.

Instead, Yakovlev says, the thinking may be that Russia’s enormous state corporations that preside over the country’s vast oil and gas wealth can provide Russia with the economic muscle it needs to grow its economy.

“It’s a dangerous illusion,” Yakovlev said.

That go-it-alone approach failed for the Soviet Union, and he predicts it won’t work for modern Russia either.

This story originally appeared on CBC