Casual filmgoers may have missed the March theatrical release of The Hummingbird Project. Although the movie’s most memorable quality may have been the sight of Alexander Skarsgård rocking male pattern baldness, there’s a small plot element that presents a significant meaning to city development initiatives.

In the film, which is based on a true story, a pair of cousins plan to create a 1,000-mile-long fibre-optic cable that allows them to shave a millisecond off New York Stock Exchange transactions, resulting in millions of dollars in profits. Their strategy involves excavating city streets to run their line through, essentially changing city infrastructure to their benefit. While it may seem like an objectionable scheme in the world of fiction, this has actually become a recurring event in several cities worldwide, with wide-reaching – and occasionally disastrous – impacts.

Google’s parent company, Alphabet, in particular has a troubling track record when it comes to working with municipalities on massive investments to transform cities into futuristic urban centres. Two cities have very recently been dealing with this issue.

Louisville

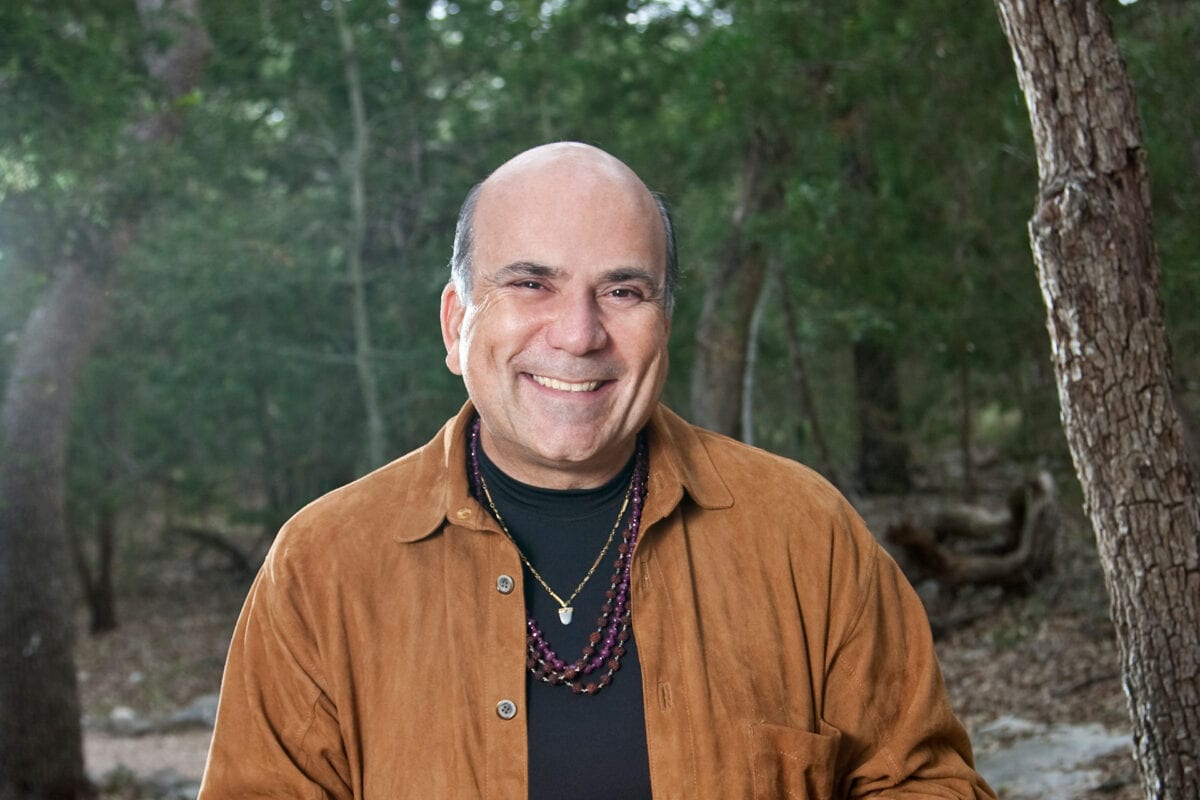

photo by The Pug Father

In 2015, Alphabet chose several cities in Kentucky to host its Google Fiber project. Google Fiber is a service providing broadband internet and IPTV directly to a number of locations, and the initiative in Kentucky closely mirrors some of the details from The Hummingbird Project. The tech giant dug up city streets to bury fibre optic cables of their own, touting a new technique that would only require the cables to be a few inches beneath the surface. However, after two years of delays and negotiations after the announcement, Google abandoned the project in Louisville, Kentucky.

Like an unwanted pest in a garden, sign of Google’s presence can be seen and felt in the city streets. Metro Councilman Brandon Coan criticized the state of the city’s infrastructure, pointing out that strands of errant, tar-like sealant, used to cover up the cables, are “everywhere.” Speaking outside of a Louisville coffee shop that ran Google Fiber lines before the departure, he said, “I’m confident that Google and the city are going to negotiate a deal… to restore the roads to as good a condition as they were when they got here. Frankly, I think they owe us more than that.”

Google’s disappearance did more than just damage roads in Louisville. Plans for promising projects were abandoned, including transformative economic development that could have provided the population with new jobs and vastly different career opportunities than what was available. Add to that the fact that media coverage of the aborted initiative cast Louisville as the site of a failed experiment, creating an impression of the city as an embarrassment. (Google has since announced plans to reimburse the city $3.84 million over 20 months to help repair the damage to the city’s streets and infrastructure.)

Toronto

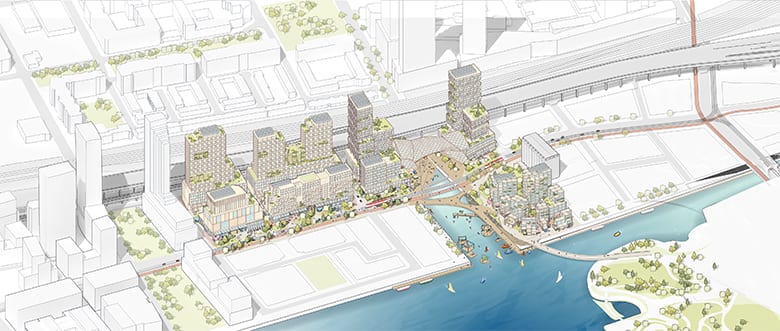

Sidewalk Labs, another subsidiary of Alphabet, joined a collaborative venture with Toronto to develop a “smart neighbourhood” on the city’s waterfront. Sidewalk Toronto promises a sleek new futuristic landscape that sounds like something from a sci-fi movie, including “hexagonal sidewalks that light up to indicate a change in a street’s usage and heat up to reduce ice and snow.” The tech giant also pledged to erect “building raincoats,” structures that can adjust overhead to provide cover from rain or snow while also opening up in warmer temperatures.

One of the world’s biggest tech companies is promising to revamp an entire area of a major North American city. So, what’s the catch? Data. According to critics, Google’s parent is seeking to turn the Sidewalk Toronto district into a “constitution-free zone.” This doesn’t mean that the lakeshore will go the way of The Hunger Games, but the implications are still concerning. While Alphabet is looking to make Toronto a test bed for cutting-edge technology, the company is also being vague about the amount of data it intends to collect from people in the high-tech neighbourhood.

photo credit: Sidewalk Labs

“We are getting closer and closer to Sidewalk Toronto being in a position where they are going to start building a part of the city that amounts to a constitution-free zone, where they are able to invade people’s privacy and collect information about them in circumstances where normally you would need a warrant to get that stuff,” Michael Bryant, general counsel for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, told the CBC in March.

Keerthana Rang, spokesperson for Sidewalk Labs, denies such nefarious intentions, calling it a “mischaracterization.” She insists the company is committed to following Canadian privacy law, adding, “we anticipate robust privacy protections that will go further than the law currently requires.”

Whichever direction Sidewalk Toronto goes in, legislators will hopefully keep the Louisville debacle in mind just in case Google’s much-vaunted transformation of the city’s lakeshore takes a negative turn.

Alex Correa | Staff Writer