The City of Toronto launched a public consultation this week on the safety of clothing donation bins, after a series of deaths across the country. Crystal Papineau was one of them — a victim of her difficult life on the streets, and her compassion for others. The National sent reporter Nick Purdon and producer Leonardo Palleja to speak with Papineau’s parents about their daughter and her life leading up to that fateful night.

Crystal Papineau grew up in a small one-storey house on a country road about 50 kilometres from Ottawa — the home where her father Gerald Kuno and stepmom Evelyn Simser still live.

She died in the early hours of a frigid morning in January, at the age of 35, pinned inside a clothing donation bin in Toronto.

“I don’t know where to begin,” Simser says. “I don’t know how Crystal ended up where she did. We had our ups and downs. But there were a lot of good times with Crystal.”

Kuno smokes a cigarette in the driveway and kicks the snow off his boots. He remembers how his daughter spent hours playing in the fields around the house when she was a child.

Crystal Papineau’s father, Gerald Kuno, holds the family portrait that hangs in the house Crystal called home until she was 16. (Nick Purdon/CBC)

Then he points to the roof.

“She used to climb on there with her cousin,” Kuno smiles. “She was fearless.”

Kuno says in the early years Crystal was always drawing and reading, too — and she loved their family camping trips.

“You always think what did you do, what didn’t you do right,” Kuno says. “So yeah, you have to only think of the good times.”

Out of control

The good times didn’t last.

As Crystal grew older her parents say her behaviour got increasingly out of control.

Simser says when Crystal turned seven she began to have “episodes.”

As a six-year-old, Crystal Papineau was always drawing and reading and playing in the fields around her family’s house. She also used to climb on the roof and dance. ‘She was fearless,’ her father says. (Papineau family )

“She’d go outside and tear her clothes all off,” Simser says. “Take a stick and beat, smash smash smash … or throw stones.

“What was I supposed to do? Grab her by the hair, throw her on her bed and lock the door?” Simser asks.

After Crystal was kicked out of school and her behaviour became too much for those around her to handle, Simser says on several occasions the Children’s Aid Society advised the family to put her in one of the group homes in and around Ottawa.

“Whenever we found that she was getting out of control, we placed her in places where we figured she wouldn’t be able to hurt herself or hurt other people,” Simser says.

“They said they would help her, too,” Kuno adds.

Looking back, it tortures the couple that they sent their daughter away.

Crystal Papineau’s father Gerald Kuno, and her stepmother Evelyn Simser, circa 1989. (Gerald Kuno and Evelyn Simser )

“They said they’d get help for her. But whenever she was in there, she’d think ‘Mommy and Daddy don’t love me. Look where they got me. They got me in here,'” Simser says.

“Any relationship Gerry and I built up with Crystal — whenever we put her in those places, that trust that she had went way down.”

When Crystal turned 16 she left and never returned home again.

A home on the street

For years Kuno and Simser didn’t know much about where their daughter was — other than she was living somewhere on the streets of Toronto.

They would only get a few phone calls a year.

Still, Kuno could imagine what his daughter was going through. He’d spent several winters on the streets himself before he was 20.

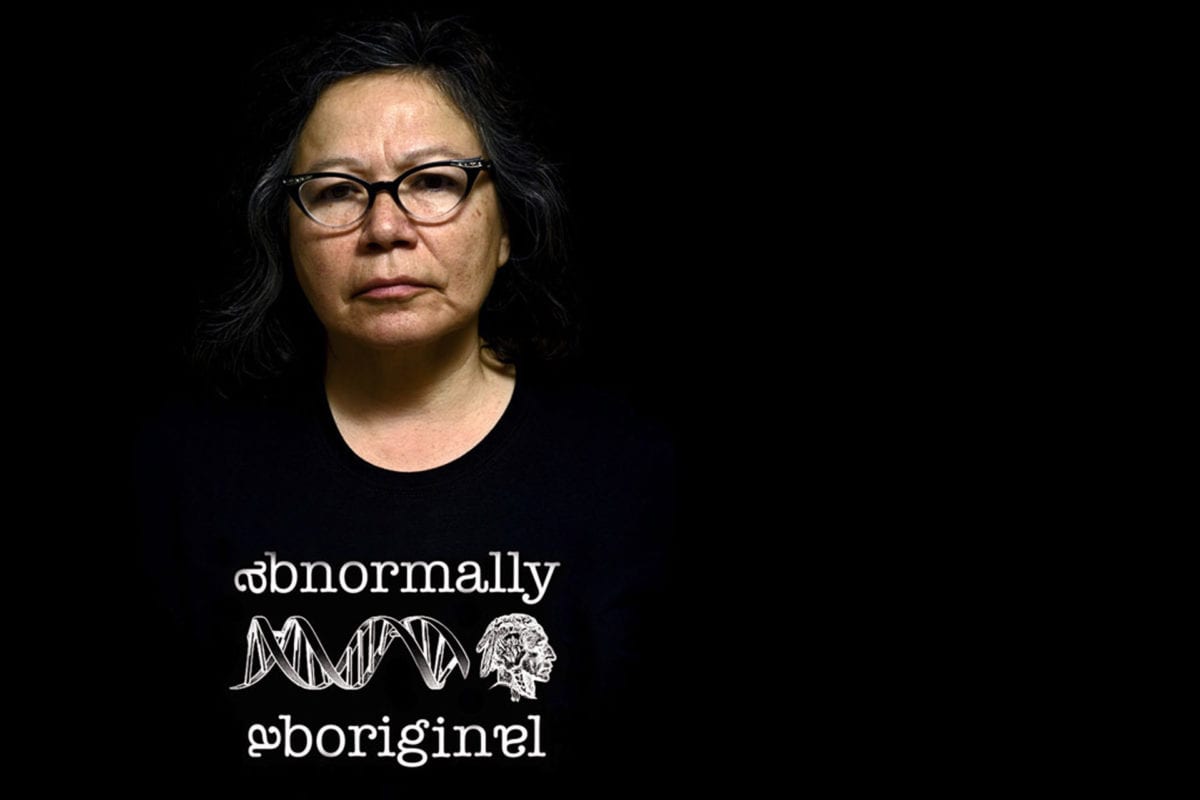

Gerald Kuno knew what his daughter was going through as a homeless person, recalling the several winters he spent on the streets himself when he was younger. (Nick Purdon/CBC)

“I know what it is like to be cold, laying in a snowbank with plastic over you,” Kuno says.

“Or sleeping in somebody’s utility room because the furnace kicks on and it’s warm. Or sleeping in five bags of garbage hoping it don’t stink so you can have some place that is comfortable. I know about that.”

Once Kuno found out where his daughter was in Toronto, he and Simser went to see her. Crystal was 19 at the time.

They found a young woman with her own ideas about the world.

“We bought her breakfast — ‘Oh, I am a vegetarian now, so I don’t eat meat. Don’t give me no money because all I am gonna do is pierce my body,'” Kuno remembers. “‘I’m glad to see you but I don’t want to leave Toronto.'”

“We wanted her to come home,” Kuno says.

Crystal Papineau, in an undated photo. ‘When Crystal needed help from other places, she didn’t get it – the only help she ever got was in the streets in Toronto,’ says her stepmother Evelyn Simser. (Papineau family )

During the visit they toured the streets of downtown Toronto and Crystal introduced them to her friends.

“The only help that Crystal got was when she went to Toronto,” Simser says. “She found people that she could help and would help her. And she felt safe with them — a lot better than she did here, because they weren’t gonna throw her out again.”

Kuno shakes his head as he listens to his wife.

“Don’t feel that way. No. You are putting it all on yourself,” he says.

“I’m telling you that’s how Crystal felt,” Simser replies as she begins to cry.

Jan. 8, 2019

January 8th was an especially cold night in Toronto.

Early that morning Crystal Papineau climbed into a clothing donation bin located near a women’s shelter she frequently visited.

Crystal often pulled clothes out of donation bins and handed them out to people on the street.

That night her generosity killed her.

Kuno says the coroner phoned him and explained how the bin’s metal jaws strangled his daughter.

“The top came down, got her on the head, and the bottom one got her on the neck,” Kuno says.

“She suffocated in there. She was there long enough she was able to make a phone call, but by the time someone found her she was already dead. Eight minutes.”

Simser shakes her head. She wants all donation bins removed from the streets.

“It’s clothes. They don’t put money in it, they don’t put gold in it,” she says. “Why are they so secure for a piece of rag?”

Proud of their daughter

Kuno says he hadn’t heard anything from Crystal in the two years before she died.

“We always got her calls — ‘Hello, how are you? I am good,’ or ‘I am going to jail,’ or ‘I am in rehab,’ or something. She always let us know what was going on.”

Still, since Crystal’s death her parents have learned a lot about how Crystal lived her life.

A memorial service was held for Crystal Papineau in Toronto on Feb. 12, where friends recalled her generosity and concern for the wellfare of those around her. (Evan Mitsui/CBC)

Now underneath their sadness, there’s something else.

“I’m just amazed at her,” Simser says. “I am proud of her. I am very proud of her.”

“I don’t care if she was on the street. I don’t care if she made a million dollars a day. She made a lot of other people happy. She had so many friends and that meant a lot to me.”

And sometimes Simser says she still feels her daughter’s presence in the house.

“It just feels like she’s talking to me sometimes when I get really down,” Simser says.

“She comes to tell me ‘Mom, I am fine, don’t worry about me,’ and I believe she is. She’s in a much better place now.”

More from CBC News

Watch The National’s story about Crystal Papineau:

This story originally appeared on CBC