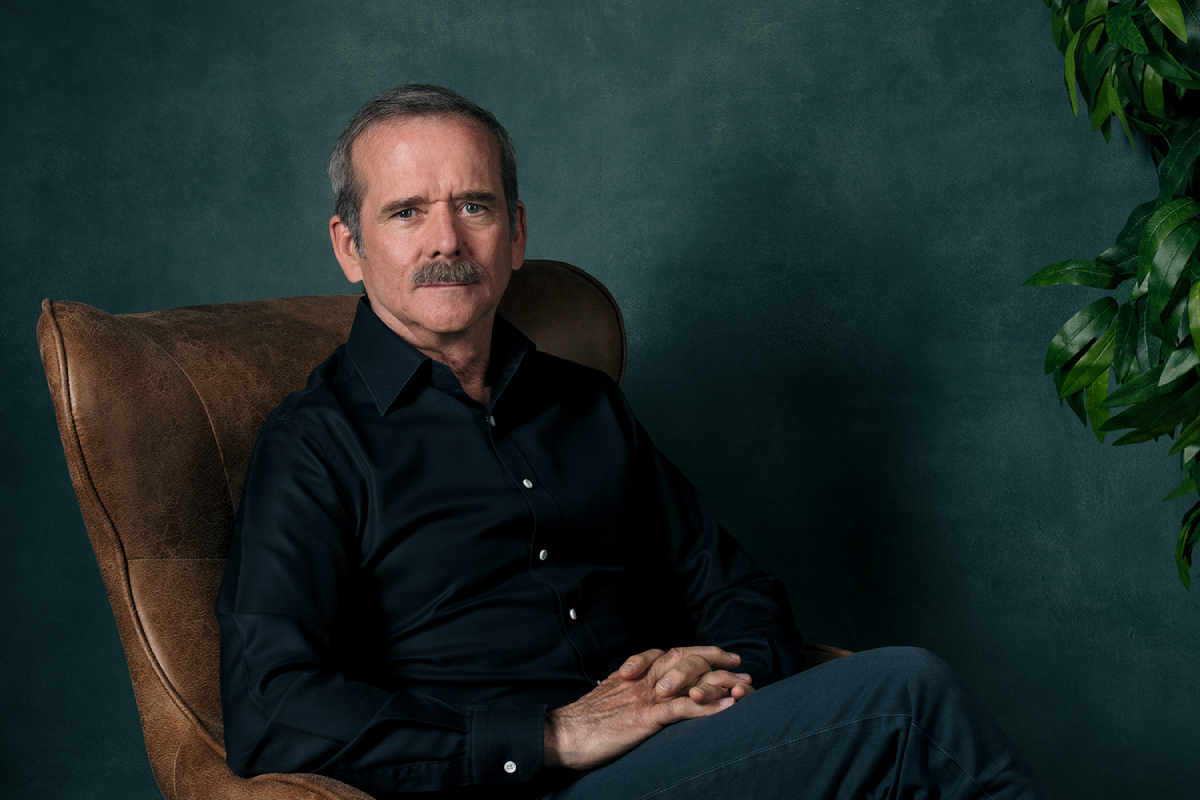

Photo courtesy of Shye Klein.

Chris Hadfield, one of the world’s best-known living astronauts, has inspired countless people with his accomplishments that include being the commander of the International Space Station, NASA’s director of operations in Russia, and a major force helping to build the Russian space station.

The seeds for his career were planted when he was nine years old. He watched the Apollo moon landing in 1969, which inspired him to earn his glider pilot’s license at age 15 as a Royal Canadian Cadet. He went on to serve a 25-year career in the Canadian Armed Forces as a fighter pilot (which included a mission to chase Russian aircrafts out of Canadian airspace!)

After a stellar career in the military, where he was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame, Hadfield embarked on a journey to fulfill his life-long dream to become an astronaut. In November 1995, twenty-six years after watching the moon landing, that dream came true. Six years later, in 2001, Hadfield would become the first Canadian to walk in space.

These days, with social media, his TED talks, and bestselling books (including the new novel The Apollo Murders), he continues to bring the allure of space down to earth for his fans.

Can you give me a quick overview of what someone who wants to be an astronaut needs to know?

It better be the thing you want to do above everything else! It’s not like a job; it’s a redefinition of who you are. It is going to take years to be selected as an astronaut. I decided to be an astronaut when I was nine and was selected at 32. I only flew in space two times, for a total of six months in [the course of] 21 years as an astronaut.

I think the most important thing better be an unquenchable burning desire to do this in your heart — not just curiosity, but an insatiable desire to try to understand the unknown — and a lifetime of academics.

An astronaut studies every day of their entire career, and it is extremely technical and complicated stuff. I had to learn to speak Russian, and learn orbital mechanics in Russian, and how to command a Russian spaceship in Russian. You need to have that focus and mental bend in order to do those things.

It’s going to take a long time, and it is not going to [be] the way you planned. And even when you think you have all your ducks lined up, the Canadian government will change policy, or the Space Shuttle Columbia will burn up, and the program will shut down for a while. There are always going to be enormous setbacks.

You have to keep a hold of your dreams and allow that to keep you making choices every day that pull you toward something, even when it seems completely derailed by the realities of life. A tenacious attitude toward life in pursuing the things that are important to you is really critical.

Just be forever driven to improve who you are, and what you can do.

Can you give me an overview of what your times in space gave us a better understanding of?

We ran about 200 experiments while I was on the space station. Our technologies led to where we are now in many different fields — telecommunications, GPS that we take for granted, miniaturization of circuitry, weather forecasting — a lot of stuff that is “invisible” but is so important. [Recent private space flights] come as a result of the decades of work I was part of, in making the technology better, safer, and simpler.

Did you notice any cultural differences, working with counterparts around the world?

The [International] Space Station is 15 nations. They all have different cultures; most have different languages or dialects. There are big cultural differences. A lot of those countries have been in bloody war with each other within the last lifetime.

We started designing [the Space Station] in the ‘80s, built it in the ‘90s, then people started to live there 20 years ago. Think of all the political winds of change that have happened even domestically, let alone internationally. Meanwhile, we are up there, representatives of 15 nations, working hand in glove all of that time. I have lots of experience with Russia because I was NASA’s director of operations in Russia.

I lived in Russia for five years. I was director for two years over there. On my third flight, I was the pilot of a Russian spaceship. I became quite familiar with Russia in the ‘90s and 2000s.

When Columbia fell apart and killed everyone on board, that would have been the end of the Space Station. If we hadn’t been cooperating with the Russians, there would have been no way to get people and things to the Space Station. Then, when the Russians had a problem with their ship a few years later, it was the American program that carried them. Even though it is complex, difficult, and you are always running into the manifestation of culture and politics, it’s added depths of strength and capability that saved the day.

When you are on a spaceship with a German, Russian, Canadian, American, Japanese — we have a lot of similarities, and we train for years and years. You watch some of the transient noisy politics and electoral cycles — and it’s real — but it doesn’t drive your daily life on a space shuttle. It’s collegial, and it has to be.

We live by a different set of laws on the Space Station — International Crew Code of Conduct — not by one individual country’s laws. It’s an interesting glimpse into the future, and what life will be like on the moon and beyond.

Dave Gordon | Contributing Writer